should advertising be abolished?

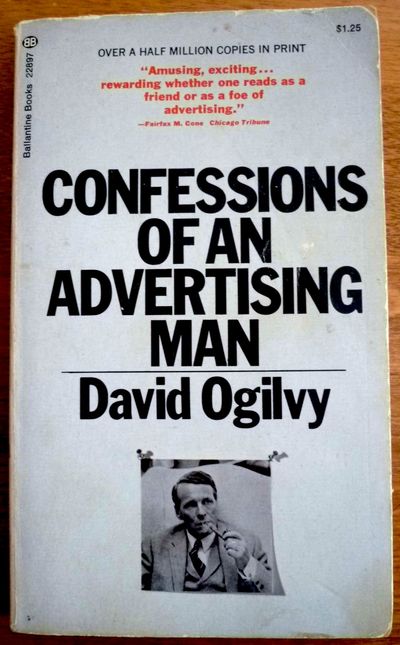

I’m on holiday in France at the moment, staying in an old house in the countryside. It was a rainy day today and on a dusty shelf I found a copy of David Ogilvy’s 1963 book Confessions of an Advertising Man. The book is a fascinating artifact of its time, a contemporary account of the reality of the world dramatised in Mad Men, containing rules for how to construct effective direct response ads and opinions on things like How to Rise to the Top of the Tree (“Do not make the common mistake of regarding your clients as hostile boobs”).

In the final chapter, which has the title that heads up this post, Ogilvy mounts a defence of the worth of advertising and includes a couple of quotes.

If I were starting life over again, I am inclined to think that I would go into the advertising business in preference to almost any other…The general raising of the standards of modern civilization among all groups of people during the last half century would have been impossible without the spreading of the knowledge of higher standards by means of advertising.

President Franklin Roosevelt

Advertising nourishes the consuming power of men. It sets up before a man the goal of a better home, better clothing, better food for himself and his family. It spurs individual exertion and greater production.

Winston Churchill

On the other hand, Ogilvy reports that Professor Galbraith of Harvard holds that “advertising tempts people to squander money on ‘un-needed’ possessions when they ought to be spending it on public works”.

Similar views are still expressed today, for example by George Monbiot in The Guardian (as previously noted here) who wrote, “To keep their markets growing, companies must keep persuading us that we have unmet needs. In other words, they must encourage us to become dissatisfied with what we have. To be sexy, beautiful, happy, relaxed, we must buy their products. They shove us on to the hedonic treadmill, on which we must run ever faster to escape a growing sense of inadequacy.”

Interestingly, though writing 50 years apart, from very different perspectives, David and George are agreed on one thing. Monbiot says:

“I detest this poison, but I also recognise that I am becoming more dependent on it. As sales of print editions decline, newspapers lean even more heavily on advertising.”

Ogilvy writes:

“You would have to pay a fortune for the Sunday New York Times if it carried no advertising. And just think how dull it would be.”

Ogilvy’s book concludes with a diatribe against the then-recent advent of “impossible-to-escape” TV advertising. He is “angered to the point of violence by the commercial interruption of programs” and says, “It is television advertising that has made Madison Avenue the arch-symbol of tasteless materialism. If governments do not soon set up machinery for the regulation of television, I fear that the majority of thoughtful men will come to agree with Toynbee that ‘the destiny of our Western civilization turns on the issue of our struggle with all that Madison Avenue stands for’… The vast majority of thought-leaders now believe that advertising promotes values that are too materialistic. The danger to my bread and butter arises out of the fact that what thought-leaders think today, the majority of voters are likely to think tomorrow… Advertising should not be abolished. But it must be reformed.”

Since Ogilvy wrote his book there have been successive waves of advertising regulation – in TV and other media. Advertising has been reformed and continues to be further regulated. But our celebrity-obsessed society is probably more materialistic than ever before. Maybe advertising is a symptom rather than the cause. Which is not to say that today's advertising, still mostly tasteless and crass, is not still in need of reform. Vive la revolution! As they say in these parts.